Community Partners

The SELCO Foundation did not have experience in the Northeast when they decided to make the region a testbed for their ideas on user-centered, ecosystem-based design. They entered as strangers in an environment where people had longstanding relationships with one another and followed traditions that were often opaque to outsiders. The Foundation realized that to be effective in helping rural households build livelihoods, they would need partners with local connections and knowledge.

Over time, SF built a partner network of 10-12 grassroots level civic organizations in the Northeast with whom they shared goals of livelihood promotion. Huda Jaffer, a SF Director, notes,

In most cases, these grassroots-level civil society bodies or smaller NGOs with which we work don't come with technical expertise. They represent the community. We look to build on their understanding of the community and their ability to mobilize, create awareness, and do outreach. These organizations complement the expertise that we have in ecosystem thinking, clean energy, and technology.

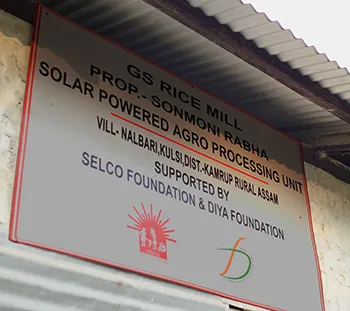

The SELCO Foundation partnered with Diya to promote DRE interventions in villages of the Northeast.

The organizations tended to be smaller NGOs. Most were too small to gain funding from larger foundations, so support from SF was greatly appreciated. These organizations provided a crucial link from system-level analysis and to local community action.

For example, SF partnered with the Diya Foundation, a group that did work in both Assam and Meghalaya. Besides rural livelihoods, Diya’s 22 full-time staff also focused on health and education.

Diya’s approach to rural development mirrored that of other small community NGOs. In the districts in which Diya operated, they identified remote communities, consisting of marginal farmers. Once a community was selected, Diya conducted a “participatory rural appraisal” (PRA), to learn about the cultivation and processing habits of farmers, noting particular issues and challenges. PRA sessions led to a dynamic exchange between villagers and Diya staff. An early advocate of PRAs, academic Robert Chambers notes,

In PRA, outsiders encourage and allow local people to dominate, to determine much of the agenda, to gather, express and analyze information, and to plan. Outsiders are facilitators, learners and consultants. Their activities are to establish rapport, to convene and catalyze, to enquire, to help in the use of methods, and to encourage local people to choose and improvise methods for themselves.1

Introducing any new technology into a village required building trust. “Taking any product or any intervention into villages, we really need to be very careful and sensitize the community well,” Martin Rabha, the Founder/Secretary of Diya observes. “Before we start, we organize meetings where the village youths, elderly, women, are present and we have a round of discussions with them, in order to build confidence.” Trust is furthered by recruiting a few pilot households to demonstrate an intervention and its utility.

Diya tried to anticipate the impact of a technology on the community’s commerce – taking care that too much additional capacity in a given locale did not saturate the available market and disrupt an adopter’s ability to earn additional income. The organization defined a cluster, consisting of the villages around a given microenterprise that a business could support. Diya also promoted its sponsored microenterprises to other households within the cluster. Diya founder Rabha notes,

We have adopted a cluster perspective to look into the business side. We consider how many villages or households one rice huller unit will serve. We follow this process with huller units, egg incubators, Eri spinning units, and so on to keep out the push and pull in the business activities… That’s how we look at the forward linkage. When we come to the business part, we ensure the survivability of those units.

Diya also made sure that the technologies kept working post-installation, with weekly contact with recipients of the new technologies. Rabha observes,

We follow a very strict process of following up with these entrepreneurs in order to make sure the systems are running well. We have meetings and make phone calls. Also, we have various kind of business-related discussions where we join up entrepreneurs in a particular village in order to have cross-learning. We look at who is doing well and who is not doing well and how they can learn from each other, and also how the solutions can be made better.

SF used a variety of methods to find community partner organizations like Diya. The Foundation held state and national level workshops with grassroots NGOs that yielded a number of potential partners. Other NGOs read about SF’s work and reach out to the foundation. In a few cases, SF incubated community organizations. The Foundation’s Jaffer recounts how SF helped MOSONiE, a partner organization in the Northeast come into being,

A local college called for a contest of grassroot champions/ideas. The founder of MOSONiE was one of the shortlisted people, and Harish was a judge. That's how we found her. When we started, she was just an individual who had an idea. We worked with her, and she built a team of seven women who go to the villages every day and just carry out some amazing community engagement work in very, very difficult regions.

Besides material support, SF provided MOSONiE with advice and guidance. Liinai Margaret, the founder of MOSONiE, refers to SF as “the parents” of her organization, noting “they have been supporting us since the initial stages, till now. They have backed our team costs as well as the program costs.”

Footnotes

- 1

Robert Chambers, “Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Analysis of the Experience,” World Development, 1994.